FOR THE CHOP IN CIUDAD JUAREZ

Drug-war diary: part one

The Times, Borderline Beat, InSight Crime, Metro, 2010-2013

The British are a nation of rubberneckers: we chase ambulances as though they're ice-cream vans, and our paramedics play to packed houses. But here, on the US-Mexico border, a curious nature will get you more than a close-up. Gawpers are in short supply where blue lights spell danger. At the first sound of a siren, people scatter or turn their backs – figuring it’s better to face the wall, lest, seeing something they shouldn’t, they wind up sliding down it

Welcome to Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua; population… dropping. This year, having outgunned every free-fire zone in Brazil, Honduras and El Salvador, Juárez was declared the “Murder Capital of the World”. No thank-you speeches were made or awards pressed to bosoms but, if its recent body count is anything to go by, the city has embraced its newfound status.

You wouldn’t know to look at it, though. During daylight hours, Juárez could easily pass for Just Another Mexican Border Town. Wherever you turn, there are dust-globe scenes of hustle and stupor, of ornament and excrement, of saguaro green and that shade of blue that must be in the gift of muralist angels because it’s not available in tins.

Its neighbours over the way, in El Paso, Texas, know better, of course, and they don’t come around much any more. I couchsurfed in that for-the-most-part peaceful, prosperous city for a few days before heading into Juárez, drinking small-batch beers in its hipster establishments – its arcade bars and hookah lounges – and talking to its students. Twenty years ago Juárez was a way to spend a weekend. Now it’s a dare, a test of freshman nerve. And few take it. Not that I didn’t hear plenty of stories about strip club misdemeanours, drug deals gone wrong and escapes on foot in threadbare Converse, but they were just skits; unlived, unloved things lacking the details – names and dates – that give reality away. “The Juárez trip” has become its own subgenre of YA fiction.

The US State Department estimates that 90 per cent of the cocaine that powders American noses comes through Mexico. It used to get the executive treatment, arriving by air and sea – dropped off by Cessna-borne Medellín mobsters in Del Monte cotton; picked up by narco boats in fishing trawler drag – but outsmarting the South Florida Task Force, though not difficult, became too costly (unsurprisingly, given the Force, when it was established in 1982, was the most expensive drug enforcement operation in US history).

The goods have travelled mostly overland since the late Eighties, and Mexicans have handled their end of the business for about 25 years. Whether it is first slow-boated from Colombia to a friendly Mexican port, or hard-schlepped through the Darién Gap and Central America, the white stuff goes by ground now.

Organised crime in Mexico – and the widespread political corruption (that is, institutional failure on a Busby Berkeley scale) that supports it – had been looking to make proper money for a while. Marijuana, the country’s traditional contraband, simply wasn’t cutting it, and heroin back then wasn’t nearly as popular in the States as it is now (few foresaw that vast tracts of Chihuahua, Durango and Sinaloa would be turned over to poppy cultivation to serve a generation hooked on – but unable to afford – prescription opioids). Cocaine was the making of Mexico’s drug cartels and they have largely stuck by it, expanding their business to include running coca base out of Colombia for refining at home (having cornered the American meth market, Mexico has the labs and chemistry knowhow, while processing facilities are being broken up and precursor chemicals becoming harder to obtain where coca is farmed).

Drugs claim lives, drug wars claim more, and the War on Drugs, which is not the same thing, more still. Mexican president Felipe Calderón launched the latter, a nationwide military offensive against the cartels, in 2006, the year he took office. Not out of a sense of affronted sovereignty, you understand, but as an affront to that sovereignty. Calderón had gone to the Bush Jr administration for help to tackle drugs and arms trafficking, and under the Mérida Initiative, a “bilateral security cooperation agreement” that was launched in 2007, the States now bankrolls the War on Drugs. So far, it has parted with close to a billion dollars and, given that money talks, it has had a lot to say about what Calderón’s battle plan should be and how it might best be executed. The United States expects a certain kind of bang for its buck – who knew?

The War on Drugs has achieved none of its stated aims – the flow of narcotics into the US hasn’t so much as slowed – and its humanitarian cost has been enormous. According to official figures (which nobody quotes in good conscience), 50,000 Mexicans have died since the War began. But this is the way America conducts its proxy wars. Its motto? Whatever the Latin is for “Make the right headlines and damn the consequences” (the US didn’t coin the term “collateral damage” for nothing).

At the behest of its sponsor, the Mexican army is targeting high-profile cartel bosses. While the deployment of this “decapitation strategy” has earned Calderón some points in the States as a malleable ally; at home it has put paid to countless innocent – non-combatant – lives and destroyed whole communities. When a drug lord is taken out, a power vacuum is created, and each capo has a dozen or more deeply paranoiac and heavily armed pretenders to his throne waiting in the wings, ready to stage a palace coup that will light up the sky like all your Independence Days have come at once.

Regardless of the orders it has been given, in many parts of the country the army simply does what it wants; tending to its own criminal enterprises, sometimes working in concert with the cartels, sometimes in defiance of them. Essentially, it’s just another player at the table, albeit one with enviable advantages, such as freedom from scrutiny, and unlimited access to firepower. In Juárez, you have as much to fear from the forces of law and order as you have from the agents of chaos. No one wears a white hat in this town.

And if it’s your turn to be shaken down, you just have to take it. It may come as a surprise to people who believe Mexico is an open asylum full of tooled-up bandidos, but the country has strict gun ownership laws. There’s one gun store – on a military base in Mexico City – and the Mexican constitution allows for legal possession of a single small-calibre handgun or hunting rifle per household, on the understanding that it is registered with the army and not carried in the street. Consequently, the American firearms industry has done very well out of Mexico’s transformation into a shooting gallery. The cartels spend their drug money on weapons in the US, then ship them across the border, often in the same vehicles and by the same routes used to bring the narcotics in. It’s a perfect circle of death.

Presidents Bush Jr and Obama have done their bit, too. Between 2006 and 2011, the US Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives allowed thousands of weapons, including AR-15s, AK-47s and grenade launchers, to cross into Mexico in “gunwalking” stings that were intended to lead federal agents to cartel safehouses. Not only did these operations – Fast and Furious, and Wide Receiver – fail to result in significant collars, most of the arms went AWOL, and when they eventually turned up it was at border zone crime scenes, such as the one in Nogales, Arizona, where a US Border Patrol agent was found shot dead in December 2010.

So how did Ciudad Juárez come by its particularly lethal reputation? Simply, “the Juárez plaza” is one of Mexico’s most lucrative smuggling corridors; the control of which is a major prize. The Sinaloa Cartel, the largest and oldest criminal organisation in Mexico, want the plaza, and the Juárez Cartel have forged an uneasy alliance with Los Zetas – a phenomenally brutal band of Special Forces defectors who were hired as mercenaries by the Gulf Cartel, only to take over most of their territory – to keep them out of it. They won’t stop till there’s a winner, however many losers that takes.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

I walked into Juárez for the first time in August 2010, after being poked about by three sets of officials. I couldn’t work out who was in charge, but the darker the uniform they wore, the more noise they made. My rucksack was emptied at my feet, its contents kicked about and my face studied. I kept my eyes on the Rio Grande. That river: its name throws up arresting images of appaloosa horses losing their hooves in a foaming roil, but its reality – a shit ribbon full of fertiliser run-off, smelting residues and arsenic – is decidedly not the stuff of John Ford movies.

A slight-shouldered guard in a light tan shirt handed me back my passport and asked if I needed directions to the bus station. He told me that “Durango, my home town is really beautiful and the bus journey’s not too long if you sleep”. I replied that I was stopping in Juárez for a while, which won me a delicate shrug and an expression containing more pity than was comfortable or polite. I took it to mean that the city had had its fill of martyrs [August, with 333 murders, would go on to be the bloodiest in its history].

As expected, the border was highly militarised. A conspicuous show of firepower bespoke nerves, like the enemy was everywhere, and watching. They probably were. It’s in the cartels’ interest to keep tabs on the police and the army, though they pay them considerable sums to rat on each other, and offer rewards for the heads of senior officers who refuse to take a mordida (a bribe; literally, a “bite”). In the months leading up to my visit, I corresponded with the writer Charles Bowden – whose book on Juárez, Murder City, I’d read recently – and he warned me that a moral compass isn’t much use in a place where money, status and fear call all the shots, and “You shouldn’t expect anyone to have your back unless they’re manoeuvring you into position.”

I had someone I felt I could trust, though: a fixer, a man on the ground, and I let him know that I’d arrived. Armando moved to Juárez two years ago to help his sister take care of her four sons after her husband was disappeared (here, as in Chile under Pinochet and Paraguay during the Stronato, “to disappear” is also a transitive verb). A taxi driver and general utility man since landing in Juárez, he was a private detective when I first met him, in Guadalajara, more than a decade before – I was working for an English language newspaper there and he was a dependable source of stories.

Armando was delighted that we were “getting the band back together”. A philosophical soul who saw detective work as his calling, he thought, quite genuinely, that we might do some good. “Look, cities are like human bodies. Finding out what’s wrong with them is the first step towards healing them. Guadalajara was a complex patient, lots of different symptoms, lots of different causes. Juárez isn’t complex. It’s not what anyone went to medical school for. A few symptoms, the same cause: drugs. Sad to say, I’m not a doctor. But I do have a talent for finding out things that I’m not supposed to know – people love to tell me secrets – so maybe I’m a confessor, though I stopped believing in God a long time ago. Something for my business card – Armando: he’ll hear your sins; God is dead.”

It took me the rest of the day to find a cheap place to stay downtown that didn’t charge by the hour. The Hotel Burciaga’s vast reception area recalled a field hospital: there were stacks of towels, water drums and several motionless bodies, their bellies pressed against the dewy chill of the tiled floor. It was fitting. The desert heat is a thug, and the parks were full of prone forms – as if some commando unit had stolen through the trees, on cushioned feet, bayonets dripping.

I was shown a room, which, with its humped bedclothes and stained flooring, suggested a poorly disguised crime scene. The woodchip was a mess of mosquito swats, their iridescence angry in the curtained light, and the headboard bore the legends of American teens who probably busted their cherries to The Cars’ first album (up to but not including Just What I Needed).

The air hung heavy and damp, like it had been walled up for a month. The help backed out of the room, his eyes fixed on his footwear. My Spanish fell on deaf ears, but I was soon to learn why. Seeing the sweat running off me, he grimaced and made what I assumed was the sign for “aircon”, his fingers dancing, but he flicked no switch and nothing came on. I was left to suppose that around noon each day, a caretaker with a crocked lung might blow through the keyhole.

Out in the street, the federal police were making their rounds in an open-back jeep. They were in good humour – I could hear laughter through their balaclavas; one of them was rocking his assault rifle like a baby. I chanced a photo, but in the time it took me to assess my effort – a smudge – the jeep stopped and I was beckoned over. I jumped to it with what I hoped came off like teenage indolence.

My summoner raised wraparound shades, and extended a hand. I could read my misfortune in it – it wanted my camera. Words, specifically the Spanish for “I am a lowly tourist with an eye for unexpected moments”, failed me. But I had reckoned without my genius for photography. It didn’t take long for the comandante’s face to soften. He had clicked through 25 studies of blistered stucco and flaking ironwork. He handed me back the camera, shaking his head, his eyes conceding, “I could take you in, but you’d never break, you devise your own tortures.”

I recounted this episode over coffee a couple of days later. Armando attempted to interrupt three times, chewing on his top lip, the moustache over it growing whiter by the second. Though slow to anger, he was gaining speed: “Joe, this won’t sound kind, but it is: you’re a fucking asshole. Obviously no one’s going to think you’re a local, but don’t pretend to be a tourist. Tourists have money and word of money gets around fast. Plus, if you’re a tourist here, in the murder capital of the world, you are in a class of one. Be honest. If they doubt you, they will run your details and see that you’re a journalist, but because you lied they’ll think that maybe you’re some sort of big-time journalist, a TV guy, someone important.”

He laughed, a lot and loud. I didn’t take it to heart. Besides, he was right. Journalistically, I was small change at best – an IOU on a bad day – and I stuck out like a thumb that had been repeatedly slammed in a car door: I’m six-three when I slouch, and the sun leaves me burnt, not bronzed. And I could see that the wrong people had already taken an interest. I’d been followed for a few hours – on foot and, at comic-cortège pace – by an ostentatiously modified black SUV. The pose was over.

______________________________

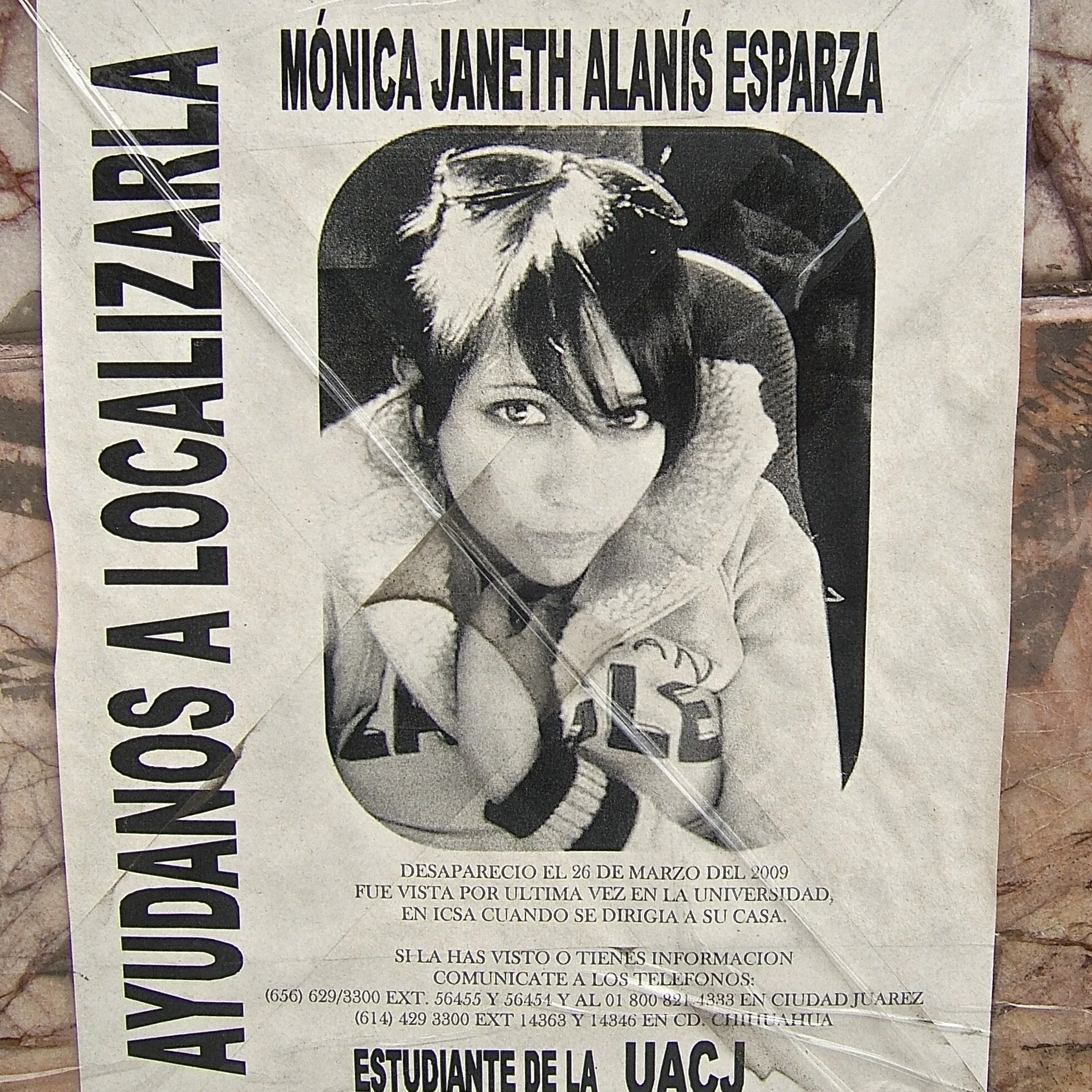

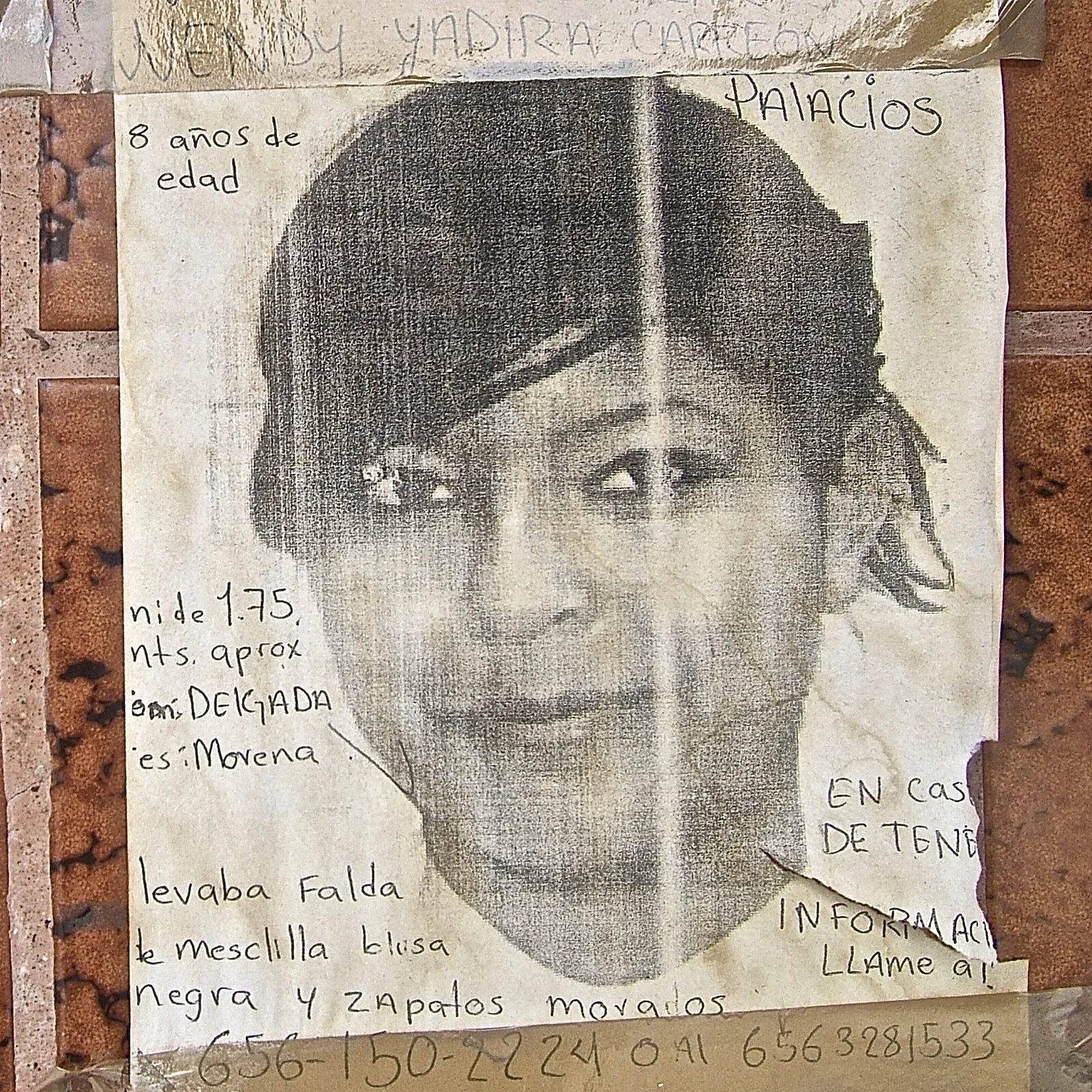

While there was little about Juárez that would have detained the careless eye, I knew what – or rather, who – I was looking for. And once I’d found them, they were all I could see. Staring out from sheets of cheap copy paper pasted the length and breadth of the city, tacked to lampposts, trees and hoardings, there they were, the women, teenagers and children; las desaparecidas (“the missing”). Parts of downtown Juárez looked like they’d been covered with torn-up yearbooks (if you’re from a deprived neighbourhood and aged between 10 and 25, you’re the girl most likely to… end up a desaparecida).

The sight should have been emptying churches and turning God to drink. Featuring loving descriptions of their personalities and little quirks (one 13-year-old, Sofia, was last seen wearing “black patent leather shoes, her favourites, though they pinched”), the posters read more like eulogies than cries for help, which wasn’t surprising: the missing rarely turn up alive.

Up to 3,000 young women and girls are thought to have been abducted, raped, tortured and murdered in Juárez since 1993, when the prospect of a job in the maquiladoras, the vast assembly-for-export plants established in the wake of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), started to draw them from Mexico's impoverished interior. A great many of those femicides are still out there, discarded like fast-food wrappers, growing more anonymous by the day; their remains, relics of a civilisation gone to hell.

To memorialise the victims who have been found and identified – and to mark the nature of their fate – pink crosses have been erected across the city, within sight of the sewage ditches, vacant lots and desert scrub where their bodies were discovered.

The success of NAFTA was built on such women – muchachas del sur – who are prized for their small hands, nimble fingers and their docility in the face of miserable wages and hazardous working conditions. Whatever is driving the murders – and my friend the Reforma newspaper columnist Sergio Gonzáles Rodríguez has described the unique weave of big business, underworld activity, male-chauvinist culture and rising drug consumption in Juárez as a “femicide machine” – the companies still enjoying the cheap labour and minimal tariffs enshrined in NAFTA seem untroubled by them. In fact, the sector, which currently employs around half a million people, is expanding. The Great Recession barely put a ding in the fortunes of Blackberry, Electrolux and Generals Motors and Electric, and their factories are swelling their ranks and offering overtime again.

Built at the city’s western limit, on the border and atop its first rubbish dump, Anapra is the poorest district in Juárez. Unfinished roads run between cinder-block shacks with chickenwire porticoes. The residents there, many of them maquiladora workers, spoke of running water as if it had magical properties. One of them, María Beatriz, had invited me to her sturdily improvised home for a plate of tamales, which she sold where I met her, downtown, between shifts. At 26, having left her home town 20 years ago and given ten years to the factories, “Eme Be” referred to herself as a “bruja”, a crone, a witch. I winced at the word, but she wasn’t having any of it.

“If I can smile, so can you. Your frown tells me my life is terrible. Showing that you are sensitive to my plight may make you feel better, but it does nothing for me. If you can’t help make my life better, then pretend to me that my life is okay the way it is.”

I apologised, and promised to take her lead, though it was difficult – her smile grew broader the more harrowing the details of her story were.

She said the work [making auto parts for Delphi Technologies] had got easier: she was putting in fewer hours for more money, and the canteen was now subsidised. But the day before the rotas were announced was a tense one.

“It’s like a lottery, but the winning ticket is also the losing ticket. The long shifts, which end in the middle of the night, pay better but no one wants to be going home at that time. Many of my co-workers sleep in the changing rooms or on the toilets, their heads resting against the stalls, till it’s light. We have all seen girls dragged into cars and stopped from leaving buses. We have heard their screams and seen them pounding on windows with their fists. A very dear friend of mine didn’t show up for work one day – no explanation, no goodbye.”

Her smile was at its sunniest, and I beamed back, but we weren’t fooling each other. “It is very frightening, even for me, and I am not what they are looking for. I had a boyfriend for a while, the son of one of my managers. I didn’t really like him – very skinny, which made him cruel, I think – but he had a car. I tell you, in Juárez, any time you see a woman holding the hand of an ugly man, it’s like they are holding a gun – it’s for protection.”

______________________________

The full story is one of systemic perfidy, as much as pure horror. The violation of the victims simply begins with their death. Their memories are desecrated by the complicity, venality, cowardice and incompetence, which, though common to all levels of government and law enforcement in Mexico, have become specialties of the house of Juárez. Despite calls from the United Nations and the International Committee on Human Rights for nothing short of institutional revolution in Mexico, criminals there consider impunity from prosecution a birthright.

In The Killing Fields: Harvest of Women, her 2006 book about a seven-year investigation into the murders, the El Paso reporter Diana Washington Valdez argued that the Juárense authorities knowingly shielded the guilty, many of whom were cartel members and prominent businessmen, and extracted confessions from scapegoats by torture, a version of events that has, for want of refutation, become fact. In 1995, Abdul Latif Sharif, an Egyptian national with a history of sex offences, was offered up by said authorities as the man solely responsible for the attacks. When his incarceration did nothing to bring down the body count, gangs of thugs were rounded up, and their ringleaders charged with murder, but not before they had “confessed” that they had merely been following Sharif’s instructions to divert the investigation away from him.

No attempt was made to clean house. Patricio Martínez García, who governed Chihuahua from 1998 to 2004, claimed he had put an end to the femicides, just like that, and railed against his critics as troublemakers. When, in 2003, Amnesty International published Intolerable Killings, its report on the state’s decade-long “failure to exercise due diligence in preventing, investigating and punishing the crimes in question”, García dismissed it as a work of fiction.

Justice may be an appalling joke in Juárez – a supervillain packing a throwdown sword and digital gram scales – but she still has her champions. Devastated mothers continue to trawl the moral morass of the border to build cases against the men who have butchered their children and when, not if, they are unable to secure a conviction, they take to the streets to present those cases, despite the painfully clear and all too present dangers posed by doing so.

In December 2010, Marisela Escobedo Ortiz, a vigorous campaigner for the retrial of her 16-year-old daughter’s confessed murderer, was gunned down outside the governor’s office in Chihuahua City. In January 2011, Susana Chávez, a poet who coined the phrase “Ni una mas” (“Not one more”), which was adopted as the rallying cry of the advocacy group Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa (May Our Daughters Return Home), was dumped – dead – in her own neighbourhood, with a black bag cinched around her neck and her left hand sawn off.

Following a week of fierce sun, the city appeared to be taking a siesta. When I remarked on this over drinks with my Juárense friends, I drew defensive fire. "Sorry, but we're not putting on a show for you – more people live in our city than die in it." I was told that foreign journalists had made the locals feel guilty; complicit and cowardly. "They ask us, 'How can you bear it?' like there is something we can do about it personally. They care about our lives only when they are over. And then they just want the basics. How tragic is a death when all anyone knows about the person who died is their name, their age and whether they ran with a gang or not? They had a favourite film, a favourite colour – they were babies once."

Paloma, my “Pal” (a lab assistant at a medical research facility in El Paso), your words still come for me at night. All journalists of conscience want to tell the truth, but the smart ones know that the whole truth is iridescent, and to pick out all its colours – and to also do justice to, let’s call it the secondary spectrum of experience and opinion – well, that takes the sort of time and money that few newspapers and magazines have to hand these days. I’m a freelancer. No one but me pays my way, but my pockets are shallow. I live – for weeks, for months sometimes – where the stories I write take place, but I know all I can offer is a snapshot. My job is not to attempt the impossible – to record “reality” – but to write well about what happened while I was looking, and to provide the proper context for it. And if I write with sufficient verve, colour and feeling, perhaps readers will want to find out more about the people it happened to.

Curled up on a park bench, partaking of the stupor that had settled on the city, I looked through my diary, hoping to find a sense of purpose between its pages. I saw that I had a date with the city morgue after lunch. I bought a burrito – first things first – then returned to my bench, the hunt for change across three pockets having exhausted me. I was barely two bites in when I realised that something was up, and everyone was looking at it. The sky – high-fired for days to a hysterical blue – had changed colour, and all of a sudden, like a baby’s face, it crumpled, and an ocean fell out of it in the time it takes to get wet.

There were good-humoured squeals as roads became rivers and prim blouses achieved transparency. Herded beneath awnings, people joked about the rain and their forced intimacy. For a moment, we were somewhere else, joined by something other, our bodies sources of coy amusement rather than menace. I took shelter in a corner store and eased my way into conversation with five middle-aged men sat on a circle of stools there.

The chat was intermittent, broken by the rain drumming on the shop’s corrugated roof, or it came in snarls about departing customers (“He had to spend some money, his trousers were too tight”). It seemed that laughter was pursued, not for the relief it brought, but the pain it caused. Doubled over like debased geishas, the men clutched their ribs or rubbed at their heartburn.

A girl of 15 or so, in school uniform, text books held over her bosom, smiled indulgently at her incorrigible uncles. She drew innuendo all the same, as did her mother and her mother’s mother, so I turned, outraged, to her critics. The man I took to be the proprietor, because he was sat closest to the counter and grabbed drinks from the cooler without glancing at the cash register, piped up: “Don’t be fooled. She drops those books in the trash as soon as she changes out of her uniform. Girls, they smile shy, innocent, good daughters, good students, but they lead double lives. Only some are prostitutes, but they all have a price.”

The atmosphere incurably soured, I ducked out into the torrent, abuse flung at my back. I had a date at the morgue, in any case. I had been encouraged to pop by with my press card – “no appointment necessary” because “people don’t stick around for long enough to require supervising”.

The registrar, Yolanda, received me with the kind of smile that suggested I was about to be shown round an apartment. And it was an open viewing of a kind. Yolanda had got a house full. Death’s latest delivery was stacked everywhere. You couldn’t move for the unmoving. It was the Grand Guignol on ice. My nose could handle the formaldehyde, and my stomach stayed put, but my pupils shrank to positions of safety.

The drug-war dead. Yolanda listed the ways they had met their maker as though she were reading meat-preparation methods off a menu: shot, stabbed, bombed, beaten, tortured, dismembered. Most of them were cartel members, a handful were in the wrong place at the wrong time: drive-by extras, accidental witnesses. Yolanda apologised for her oddly even tone but, waving her arms around as she turned full circle, she told me “you get used to it”.

Some of the horrors were so particular – spare heads, jointed carcasses, flitches of scored and scorched flesh – that I wondered what she meant by “it”, but I soon realised that it had become important for her to find a single category for all the gruesomeness on display. Professionally engaged was as human as Yolanda dared to be.

“We’re not undertakers, our job isn’t to bring the dead back to life, to put them in a suit, to arrange the flowers, to bring families peace. We bring only bad news. Parents don’t want to know what we know, to hear what horrors befell their children, to feel their pain, to learn how it was inflicted.”

Of the bodies that are identified, few are claimed. Notoriety in life begets anonymity in death – and a burial in a common grave in the San Rafael municipal cemetery. The innominate are sent off with zero ceremony, in a flash of white overalls, their memorials serial numbers scratched on a metal plate. The message is clear: no one will be waiting for you; the door to Hell is on the latch – let yourselves in.

Leaving the cemetery, I passed a stall selling gimcracks, items which, in their prime, might have gladdened it: bleached wreaths, foil windmills stilled by the humidity, and stuffed toys holding grimly wizened hearts. For the sake of the melodramatic morbidity for which I’ve always nursed a talent, I bought one for myself, a glittery star on a stick, to put in my breast pocket, and I started to compose the note I would pin to it in case I fetched up in a few weeks with a scream full of sand.

By the time I joined Armando on Avenida Juárez, the main tourist drag of yesteryear, dusk had rolled in like a dirt storm. We decided my upper lip could do with a stiffener, so we headed for the the Kentucky Club. The Kentucky opened in 1920, to mostly Prohibition-parched Texans, and its “French-carved” oak bar and portraits of Thirties matadors and beisbolistas offered sanctuary from the modern world as well as sobriety. Armando settled a Montejo with a bourbon back in front of me and took a call – I put my feet up, and let alcohol do what we pay it to do: lower the lids, warm the throat, extract a sigh. The evening approached me, holding a blanket.

That blanket was soon whipped from my shoulders. Armando returned with an indecent grin. For a month he’d been promising to introduce me to a mobbed-up acquaintance, and “Tonight”, he told me, gathering up my drinks, “it’s happening – now”.

He dragged me through the Mariscal, which begins a block west of Avenida Juárez. The former red-light district was barely twinkling. Vacant lots outnumbered the flophouses and brothels, and the vintage strip clubs – Queen’s Place, Las Vegas, the Hollywood, whose weather-eaten facades recalled the portals of bygone fairgrounds – were boarded up, dressed down for their date with a wrecking ball.

We stopped at a hole in the wall on Begonias. It was heaving. Armando spoke to a fiddle-player on the door who was dressed, in a tie-dyed loincloth and bat-wing shirt, like a psychedelic Tarahumara. He raised a palm for me to stay where I was and joined the throng inside.

Five minutes later, he reappeared, jerking his head back for me to follow him. At the far end of the bar, occupying the only stool, was Heriberto. Introductions were made. Thicker than thick-set with a tyre for a neck, “Bert” was friendly enough, but his smile, the wrong side of leery, looked about ready to take over his face. We established our bona fides over shots of mezcal. Uninterested in mine, he shook his head and unbuttoned his shirt. He flashed me a crude tattoo of an Aztec head on his left breast, nodding. I confessed its significance wasn’t lost on me (the Barrio Azteca gang did much of the Juárez cartel’s dirty work on both sides of the border). Bert took this as his cue to catalogue all the kinds of dirt he calls work, lending eye-widening definition to each and every speck of it.

Against Bert’s bulk, I could have passed for Tintin, and I’ll admit that this 40-year-old felt like a boy reporter who’d fallen under the wheels of his own ambition when I was ushered into a back room customarily used by prostitutes and their pimps, who darted out of our way like startled minnows.

Bert found a table for us – by kicking it over, sending the bottles of bleach and pot plants that were sat on it flying, and telling one of his entourage to right it again – and gestured for me to sit opposite him. Once we were settled, he reached inside his jacket, produced a glass vial of cocaine, and tapped some onto a knuckle.

“This is what it’s about,” he said, raising his knuckle, then clearing it. “Everyone’s on it, or involved in it. Doesn’t matter who you are, where you’re from. Army, police, government, banker – you’ll make more money from this. What was I going to do – work in a kitchen?

“I started out as a spotter, then handled small deliveries. I moved into debt collection, bigger and bigger amounts, first with a baseball bat – I love baseball, my cousin tried out for the [Monterrey] Sultans – then with a gun. I was good at it, very calm, serious features, you know, and I never helped myself.” He held up the vial. “Want a bump?”

In a mistaken attempt to show willing, I took it, and four snuffs and twenty minutes later the conversation began to derail. Bert was showing off, enjoying the space people made for him and the gag his reputation stuffed in their mouths. I felt I should be doing more than nodding along like his idiot consort. I excused myself to freshen up, reaching the bathroom by some unrecorded means, and flicked water at my face, imagining my heartbeat slowing to a fierce gallop. The sounds of insufflation filled my ears, as though I were standing inside a rolled note. I hung out by the sinks, looking less casual by the second, but I managed to drop down a couple of gears, and resolved to return to my seat.

By the time I did, Bert’s mood had darkened: “Do you want me to tell you about my life, or do you want me to show you?” I did not want him to show me. Bert was a sicario, a cartel enforcer with special responsibility for hostage-taking and -detention, blackmail and extortion. He stopped collecting debts 10 years ago – to collect people, though he made it clear that his collections were of only temporary value.

“We take whoever has something we want. That can be money, influence or information. We don’t deal with arseholes – junkies, loudmouths, guys who can’t keep their dick in their pants, girls who can’t keep their pussy dry – they can be shot or stabbed in the street, and left for someone else to clear up. Our dealings are with important people, businessmen, cops, prosecutors, judges, politicians and, naturally, our enemies [the Sinoloa cartel].

“We take them to a safe house. Safe for us, anyway. We have many. Some are isolated, rural; others in industrial areas – busy, loud places. Because sound carries. In the country, we tell the police to take a holiday – a week, a month, the rest of their lives – and promise to give them a good time when they come to town. Then we get down to business. The hostages, we have to fuck them up a bit, show them we’re not messing around, then we photograph or film them and call their families, friends or business partners to make our demands. With luck, in about a week, we come to an agreement that suits us.”

Bert admitted that he had grabbed the wrong person before, or the right person who turned out not to be. “Mistakes have been made. Intelligence has been faulty. And when people are in a position to help us, it can take a lot of time for their associates to find the right papers – deeds, enough money, you know. Time isn’t something they have. My bosses are impatient. And the longer we wait, the more likely it is that we’ll get careless. We get drunk, we get high, we let our guards down, our masks slip. The party has to end for anyone who can identify us.”

The less co-operative the abductee, the uglier it gets for them. Torture is standard, and medieval methods of it – Inquisition favourites such as the Judas cradle (a “pyramid” seat that people, bound and weighted, are lowered onto) and strappado (suspension by the wrists tied behind the back) – not uncommon. Doctors are kept on hand to ensure the burnings, floggings and water-boardings come in non-fatal doses.

“If there’s a chance that someone will talk, we have to keep them alive. It is unfortunate for those who have nothing to tell us. We prefer not to kill, unless it’s to protect ourselves, because getting rid of the bodies is hard work. We keep a record of who is buried where, but it seems wherever we dig, we strike bone. We are not the only ones dumping bodies, of course. The desert is full up! Like a popular hotel: no vacancies.”

The casualness with which Bert’s words tumbled out of his mouth chills me still. Murder, merely a laborious encore to a month’s rollicking entertainment. But his smile fell suddenly, and his eyes lost the lustre they’d borrowed from a bottle of tequila and an eighth of cocaine. I couldn’t help but wonder what I had coming. I had been watching the doors for a while, ears twitching for the sound of cars pulling up, all the while trying to read the body language of Bert’s coterie of wired goons who were filtering in and out of the room, miming usefulness, bumping into drinkers to make their presence felt and flashing the hardware tucked in their waistbands. Running on mutual distrust, and inured beyond boredom to their own inhumanity to man, their intentions were difficult to gauge. I played out scenarios in my head, made my peace with a quick death, and considered how best to make that happen. I wasn't about to be taken off to a house in the hills, made a plaything.

As though reading my mind, Bert switched subject, from the disposal of bodies to their display. “Sometimes we have to make an example of someone. It could be one of theirs, one of ours, and not just one. Depending on what they have done, we might cut off their head, tongue, hands, feet or cock, make a feature of them, mount them on a fountain or hang them from a bridge. We once filled a giant ice box with heads! And if passers-by wonder what they have done to deserve such fates, we leave a sign that spells it out, like in a museum! A warning to wannabe thieves. Or traitors.”

Paranoia and treachery go hand in hand. But if a traitor’s fate is to end up spreadeagled and mutilated, the centrepiece of some diabolical tableau mourant, you would hope that it would take more than idle rumour and class A drugs to find someone guilty of it. My anger rose, but expressed itself as polite inquiry. “Tell me, Bert, what value do you place on life; not a life, his life, her life, even your life – just life?”

I waited a couple of beats to be plucked from my chair, but Bert’s head was hanging, and no orders came from him, no nod, no grunt. At length, looking up slowly, he asked me if the name Hugo Hernandez meant anything to me. It didn’t. “He was a very old friend. Murdered by Sinaloa pigs. He was cut into seven pieces. They sliced off his face and stitched it to a football. Left it for children to find. Animals. We wouldn’t do that.”

Bert looked deeply conflicted. He either knew he was lying, or that the truth had forsaken him. His shoulders, so easily convulsed by gallows humour earlier on, had slumped. The worry that I might make my end that evening started to break up. With infinite care, I rose from my seat, and no one moved. I said, “Thank you for talking to me, Bert” and tried not to look at the door as I put my hand on his shoulder, giving it an uncertain squeeze for want of something suitably final to do.

I was three blocks away by the time I realised I’d left the bar, and I was alone. I didn’t know whether to cry or laugh, so I did both. Hysteria was mine. I knew that Bert’s confession – for that is what it was – would colour my nightmares for years to come, but that meant I was already contemplating the future, and for a while there I thought it had been cancelled.

I didn’t trust the staff at the Burciaga – my door had been tried several times, without a knock – so I gave sleep a miss, but there wasn’t much left of the night anyway. I bought a coffee for company, sat in the Plaza de Armas and watched the day begin to compose itself. An hour later, Armando, relieved to see I was unaccompanied, came bounding towards me. If we’d hugged for any longer, we’d have been told to get a room.

He had been waiting nervously for my call with his ear pressed to a police scanner he had retrieved from a toy-piled corner at his sister’s place.

“I was confident I wasn’t walking you into a trap. But Bert is unpredictable. He’s arrogant, but he isn’t stupid. He knows he’s not invincible, and what he described to you is probably what’s going to happen to him. Especially if he keeps talking to journalists! That’s why his mood changed maybe. He understands that everyone is expendable.

“I talked you up. Said you had a lot of eyes on you. That the world was watching! That it would be a big hassle to kill you!” We laughed. Armando could have read me my obituary and I’d have laughed.

Moments later, he was back on his mobile. Something had got him excited, and he took off at speed, with me in pursuit. I had barely got inside his Nissan, the passenger door hanging, when he put his foot through the accelerator. There had been a shooting in Colonia Aldama, a half-built, low-rise neighbourhood in the southwest of the city. Armando committed at least nine moving violations to get us there, but the emergency services had beaten us to it and the area was being taped off.

There was no mistaking the slumped forms of two men inside a bullet-pocked Dodge Ram with a Texan plate and shattered windscreen, their heads abut and their mouths open, as though they were trying to rescue an awkward first date when their killers opened fire.

A few onlookers cast bold shadows in the picnic sunshine, and there was a photographer, Virgilio, who worked for an agency. He offered a sardonic commentary.

“Look at this. Cops with sad faces, doing their duty. Bullshit. Whenever they can get away with it, they beat us up and smash or steal our equipment. This is my fifth camera in two years, my eighth cell phone. But it’s not like I’m providing a service for the people. It’s the cartels that want the pictures, not the papers. Something for their wall, to show their kids – look, our favourite hits!”

I asked him why he bothers. And got what has to be the default expression of the non-criminal class in Juárez – a rueful smirk tucked deep inside the cheek. “I have high blood pressure and a weak heart. They will get me before any bullet. Until that happens it pays pretty good.”

Photos of the double homicide in Almada appeared in Norte de Juárez a week later, but there was no story, just captions. Squeezed alongside images of other executions. A gallery of unmediated gore – more a cautionary tale, like a doom mural in a Norman church, than hard news. But the cartels continue to target journalists. Shocked by the murder of one of its rookie photographers, a 21-year-old, at a busy shopping mall on September 16, El Diario, the newspaper with the biggest circulation in Juárez, ran an editorial – an open letter to the cartels, really – with the headline: “What do you want from us?”

In gagging the press, the cartels have denied the people of Juárez their last crumb of comfort: the knowledge of how bad things really are.

Postscript: six weeks after I last saw him, Armando moved his family to Zacatecas state. He had received threatening phone calls. He offered no details except to say that his encouragement of a certain journalist had not been welcome. Armando was philosophical, but the episode brought home to me the dangers to which journalists routinely expose those who help them.